Material Balances¶

When you want to know how things really work, study them when they’re coming apart.

—William Gibson

Terminology¶

First, let’s remind ourselves of the terminology for process variables .

Exercise

Consider a process for converting chemical species, according to the reaction stoichiometry \(\ce{A + 3B -> 2C}\).

Stream 1 has the following properties:

\(\dot m\), \(\dot n\), \(\dot V\)

\(\dot n_{A}\), \(\dot n_{B}\), \(\dot n_{C}\)

\(x_{A}\), \(x_{B}\), \(x_{C}\)

\(\rho\), \(P\), \(T\)

At steady state, which of those properties will be the same in stream 2?

Why?

Does the process matter?

First, as individuals, write down your answers. Then, discuss your answers with students around you.

Conservation laws

From Wikipedia: Conservation laws are fundamental to our understanding of the physical world, in that they describe which processes can or cannot occur in nature. In general, the total quantity of the property governed by that law remains unchanged during physical processes.

Exercise:

Which of these are conserved during ‘normal’ CBE processes?

total energy

total number of moles

moles of a given species

mass

Overview of solving material balance problems¶

Let’s begin with an overview of the approach to solving material balance problems. We’ll then cover methods for specific classes of problems.

Decision tree¶

Thus, the following questions will lead you through that decision tree:

Is species information required, or will a total balance suffice?

If species information is required, are there formation/consumption terms?

If there are formation/consumption terms, is the reaction stoichiometry known or unknown?

The control volume¶

First, let’s define a very useful term in CBE: the control volume.

A control volume is a volume fixed in space or moving with constant flow velocity through which the continuum (gas, liquid, or solid) flows.

It is essentially a region in space that we define to conduct a particular process analysis.

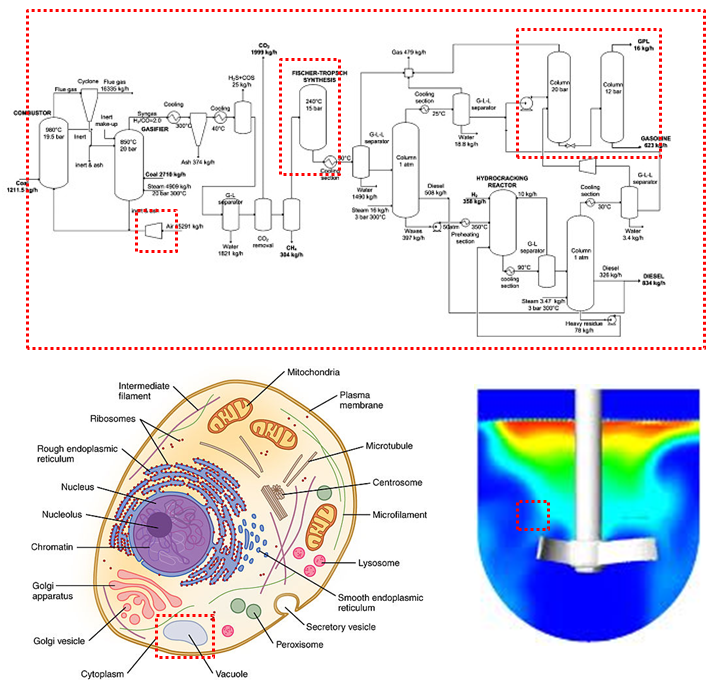

Our control volume could contain…

an entire process

a particular unit operation (heat exchanger, reactor, separator, …)

a series of unit operations or subprocesses

a small volume within a process

It is very important to define your control volume when analyzing CBE processes.

Where can we apply material (and energy) balances?¶

The material and energy balances (and other conservation laws) we will develop can be applied to almost any control volume.

Essentially, we can apply these balances whenever our control volume has inputs and/or outputs and we have some idea of what’s going on inside this volume.

Material balance equations¶

In the equations below, we can think of the system as being our control volume.

In words, the fundamental mass balance equation is

Rate that Rate that Rate that

mass enters = mass leaves + mass accumulates

the system the system in the system

In this course, we will focus primarily on systems at steady state. This means that relevant system properties do not change over time. Under these conditions, our material balance equation becomes

Rate that Rate that

mass enters = mass leaves

the system the system

Consider the following process with input and output streams:

At steady state, the governing mass balance equation would be the following:

More generally, we have the following relationships.

Fundamental mass balance equation

or

Material balances equations for multiple species¶

In the general case, the expression for the material balance on a species \(\ce{A}\) that is part of a mixture is

Rate that Rate that Rate that Rate that Rate that

A enters + A is formed = A leaves + A is consumed + A accumulates

the system in the system the system in the system in the system

For steady-state conditions, this becomes

Rate that Rate that Rate that Rate that

A enters + A is formed = A leaves + A is consumed

the system in the system the system in the system

Expressing this steady-state relationship mathematically, we have

Mass balance equation for an individual species

where

\(R_{\text{formation, A}}\) = rate that species \(A\) is formed, in units of \(\si{mass/time}\)

\(R_{\text{consumption, A}}\) = rate that species \(A\) is consumed, in units of \(\si{mass/time}\)

Making use of relationships between our process variables, we can write this equation as

or

or …

Note that the above equations should be written for one species at a time.

Material balances: No species formation or consumption¶

A number or important problems in chemical and biological engineering do not include formation or consumption.

Exercise: Species mass balance with no formation or consumption

Two chemicals \(\ce{A}\) (desired) and \(\ce{B}\) (undesired) are partially separated using a chemical separator.

The feed stream has a flow rate of \(\SI{100}{kg/hr}\) and contains \(\ce{A}\) at a mass fraction of \(0.20\), with the balance being \(\ce{B}\).

Furthermore, \(\SI{98}{percent}\) (by mass) of \(\ce{A}\) in the feed stream leaves in the product stream.

In the waste stream, the mass flow rate of \(\ce{B}\) is \(\SI{65}{kg/hr}\) .

What are the mass flow rates of \(\ce{B}\) in the product stream and \(\ce{A}\) in the waste stream?

Use our problem solving approach.

Guidelines for solving material balance problems involving multiple species

From pg 76 in Introduction to Chemical Engineering: Tools for Today and Tomorrow (5th Edition):

Determine if species information is required, or if an overall mass balance will suffice. Note: Problems involving multiple species require species information.

If information on a particular species is required, write the balance for that species first. It may be that a single-species equation will provide enough information to solve the problem.

Use species mole balances rather than mass balances if the reaction stoichiometry is known.

Do not attempt to balance the total number of moles for reacting systems if the reaction changes the number of moles.

A total mass balance is frequently useful to determine a missing flow rate for systems where the densities of the input and output streams are approximately constant. The constant-density assumption is applicable to liquid systems that contain a small amount (small concentration) of a reactant or pollutant or dissolved substance such as a salt.

Words like consumed, formed, converted, reacted, produced, generated, absorbed, destroyed, and the like in the problem statement indicate that consumption or formation term are required in the material balance. Systems that include chemical reaction always require formation and/or consumption terms.

If a single species balance does not provide sufficient information to solve the problem, write additional material balances up to the total number of species. If there are still more unknowns than equations, look for additional relationships among the unknowns, such as

Given flow rates or ratios

Fractions (mass or mole) of all species in a stream must add up to \(1.0\)

Stoichiometry: if the process includes a chemical reaction.

Conversion: if it is known that a certain fraction (\(X\)) of reactant \(A\) is converted (or consumed) in the process, one can write that the rate of consumption of \(A\) equals that fraction of the total incoming flow rate of \(A\).

Carry units as you work the problem. Calculation mistakes are frequently discovered as you try to work out the units.