|

We combine advanced theories and computer simulation techniques to study at nano- to meso-scales (i.e., from sub-nanometers to micrometers) the behavior of nanostructured polymeric materials. We are currently working on self- and directed assembly of block copolymers, stimuli-responsive polymer brushes, polyelectrolyte adsorption and layer-by-layer assembly, and structure and properties of polymer nanocomposites. We are also working on fast Monte Carlo simulations and coarse graining of polymeric systems. All of these are at the forefront of nanoscale polymer science and engineering and have important technological applications in many fields.

A characteristic of complex fluids such as polymers is that they span over largely different time and length scales (e.g., 10-12~100 s and 10-10~100 m). We therefore use a suite of computational tools, ranging from particle-based molecular simulations (molecular dynamics, Monte Carlo simulations, dissipative particle dynamics) to molecular-level theories (field theories, integral-equation theories, density-functional theories) to mesoscopic simulations (e.g., phase-field modeling and cell dynamics simulations), to investigate both thermodynamic and dynamic behavior of polymeric systems. The overarching goal is to establish the interconnections between these results at different levels, thus enabling hierarchical modeling bridging various time and length scales.

|

|

Self- and directed assembly of block copolymers

|

|

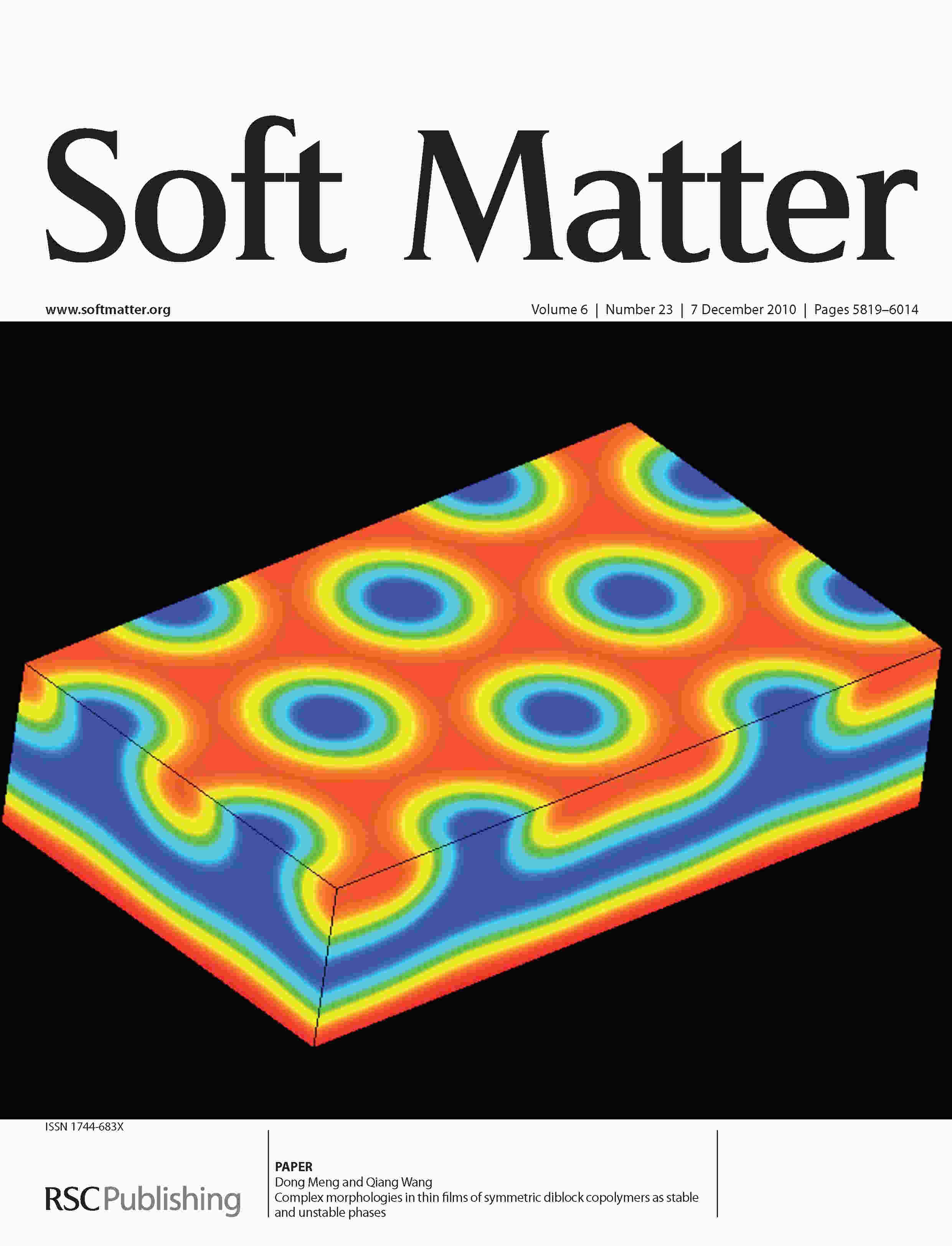

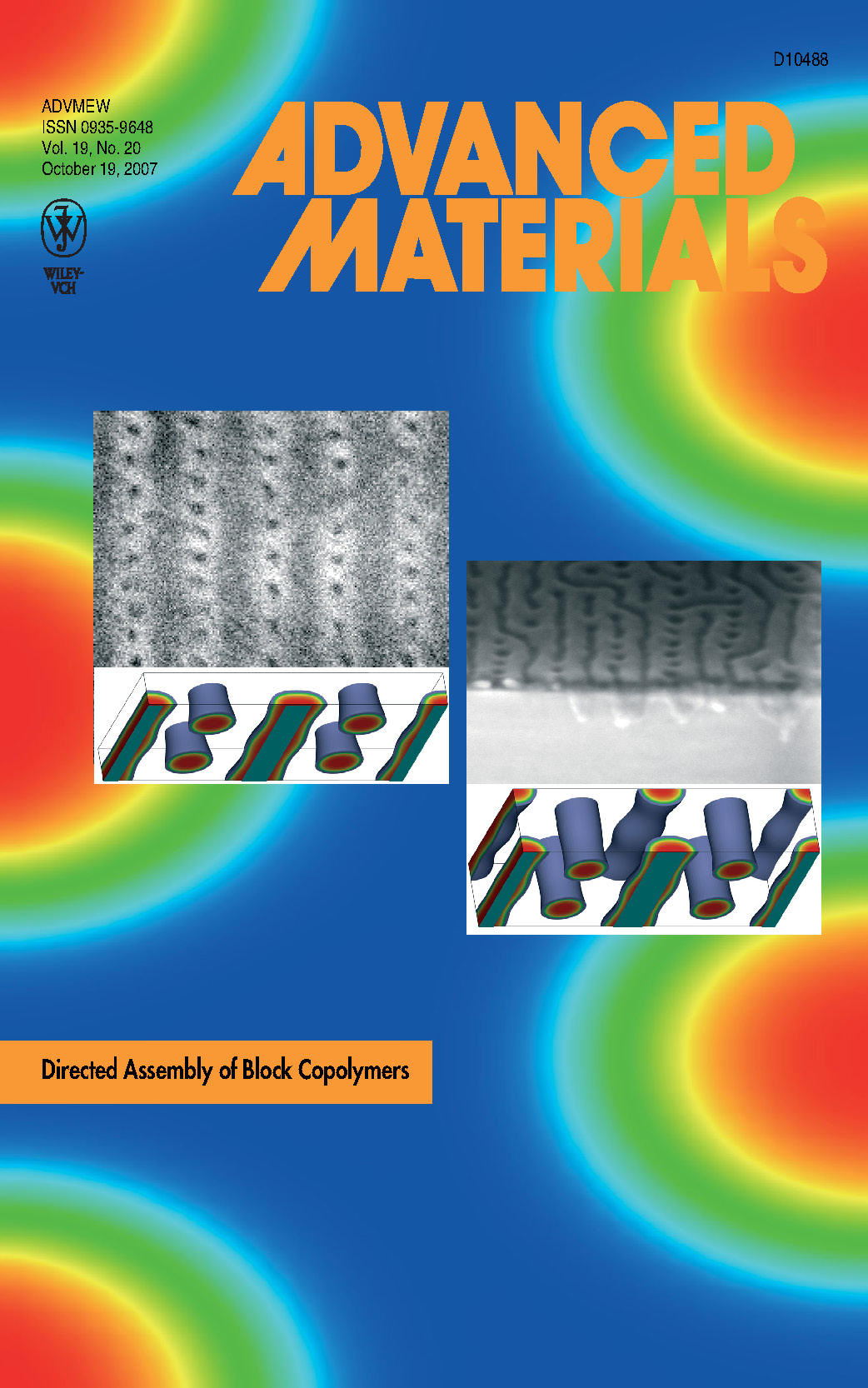

| Block copolymers (BCPs) have great potential for applications in nanotechnology, due to their self-assembly into spatially periodic structures on the length scale of 10 to 100 nanometers, direct control of the size and shape of these nanostructures, and uniformity of these nanostructures.[1,2,3] Many applications (e.g., templates for nanolithography, nanowires, high-density storage devices, and nanostructured membranes) envisage thin films of BCPs supported on a substrate, and well-ordered nanostructures oriented perpendicular to the substrate are desirable. Unfortunately, due to defect formation and slow kinetics common in BCP systems, the order of their self-assembled nanostructures persists over only a few hundreds of nanometers. Control of both the perpendicular orientation and the in-plane ordering to achieve well-ordered nanostructures is therefore the key issue in many applications of BCPs. In our original DOE project, we have studied directing block copolymer assembly by external fields (including topographically and chemically patterned substrates, and electric field) to obtain well-ordered nanostructures, using a high-performance, parallel FORTRAN 90 code (PolySCF) for 3D real-space self-consistent field calculations developed in our group. This work allows knowledge-based rational design (instead of trial-and-error experiments in a large parameter space) to obtain well-ordered nanostructures of BCPs. |

|

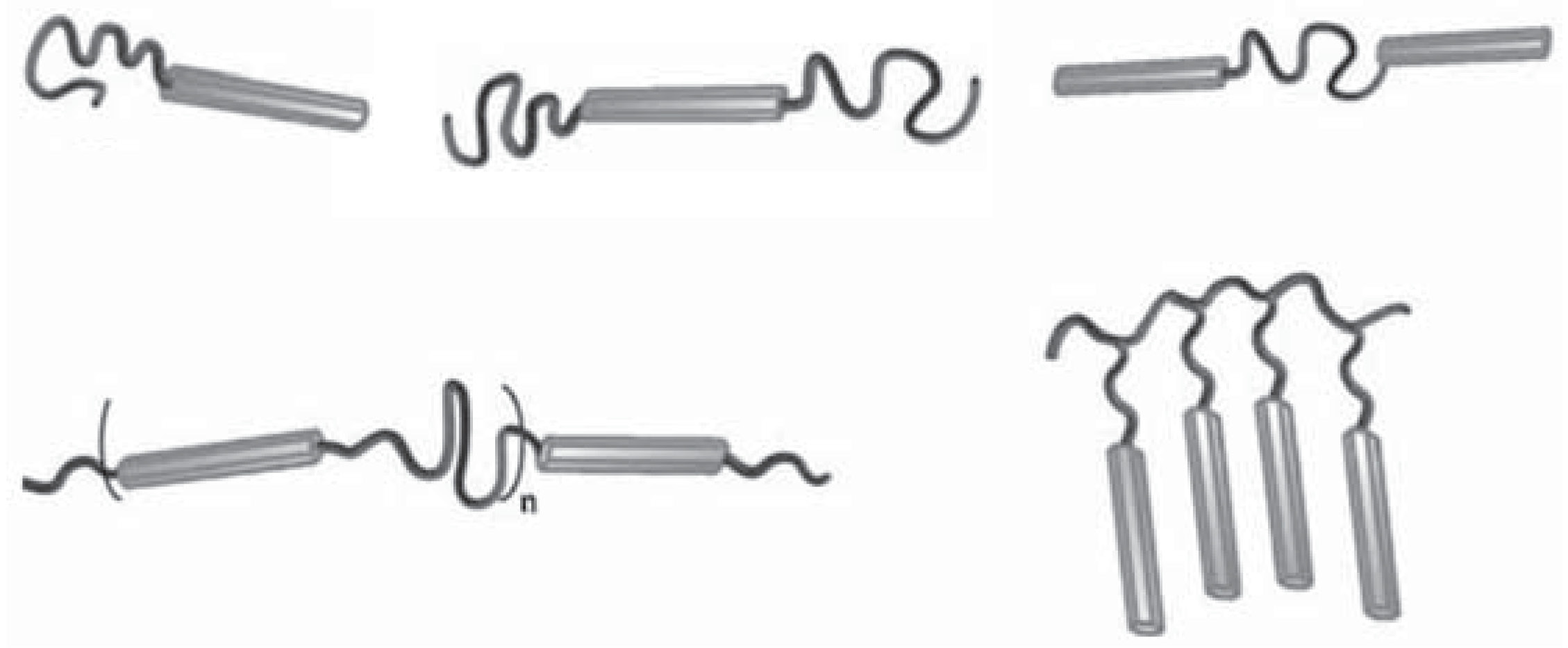

| Photovoltaic energy obtained using conjugated (semiconducting) polymers is very attractive due to its cheap materials, low processing cost, and ease of large-scale manufacture. Control of the polymer morphology and structure on the nanoscale is critically important for optimizing the efficiency of polymer optoelectronic devices.[4,5,6,7] Such control can be achieved with magnetic-field directed assembly in thin films of rod-coil (RC) BCPs containing conjugated rod blocks. In our renewed DOE project, we use both PolySCF extended to RC BCPs and the newly proposed fast off-lattice Monte Carlo simulations with soft potentials that allow particle overlapping[8] to understand, predict, and ultimately control the self-assembled nanostructures of RC BCPs in bulk, under thin-film confinement, and with applied magnetic field. This work will allow knowledge-based rational design of these nanomaterials, thus advancing their integration into a range of technologically important applications, including the fabrication of polymer-based photovoltaic cells, light-emitting diodes, field-effect transistors, and chemical and biological sensors. |

|

|

|

Stimuli-responsive polymer brushes

|

|

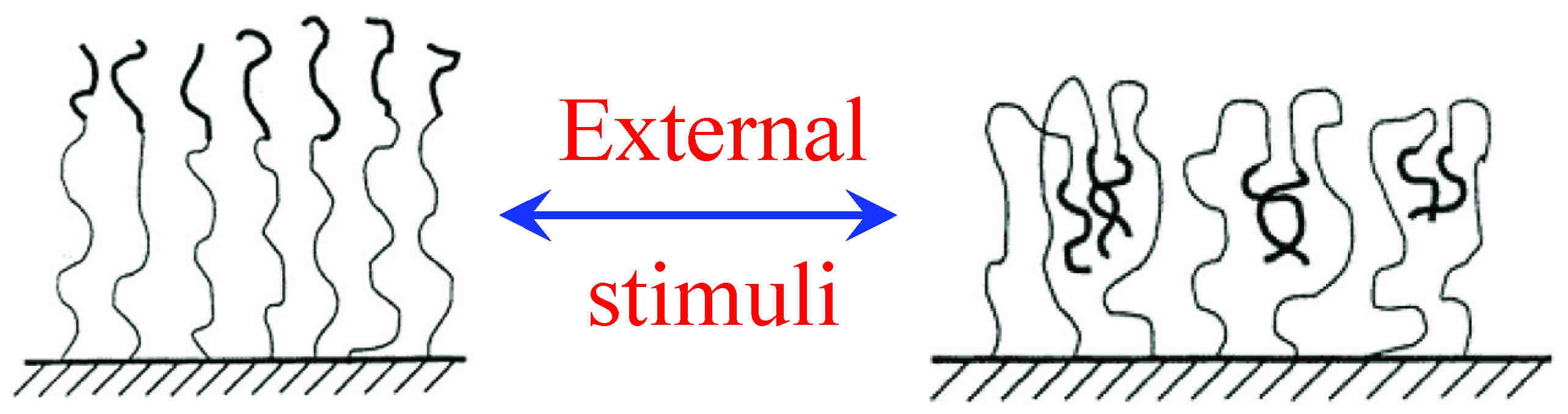

| This NSF CAREER project is a computational study on the response of two-component polymer brushes, particularly the polyelectrolyte brushes, to various external stimuli (solvent selectivity, solution pH, ionic strength, and applied electric field) and the influence on such response by various design factors (chain architecture, polymer/block lengths and charges, grafting densities, and incompatibility between the two components). The seemingly simple two-component brushes (including both binary homopolymer brushes and block copolymer brushes) can exhibit a rich variety of interesting and novel behavior through self-assembly of the two components, and have diverse applications in many fields as "smart" surfaces.[9,10,11] The design of these responsive brushes for practical applications such as chemical gates, sensors, biomaterials, and drug delivery, however, requires detailed understanding of the physics of their stimuli-response and knowledge of how various design factors affect their stimuli-response, which are rather limited. |

|

Here we use coarse-grained models describing the generic features of two-component brushes, and two judiciously designed and complementary methods: 3D parallel self-consistent field calculations and novel fast Monte Carlo simulations[8,12], which capture the physics of stimuli-response of two-component brushes and can provide essential guidance to experimental design of such smart surfaces. This work provides us with fundamental understanding and predictive capability on the stimuli-response of two-component polymer brushes and enables knowledge-based rational design of such smart surfaces best suited for targeted applications, while avoiding both labor- and time-intensive trial-and-error experiments.

|

|

Polyelectrolyte layer-by-layer assembly

|

|

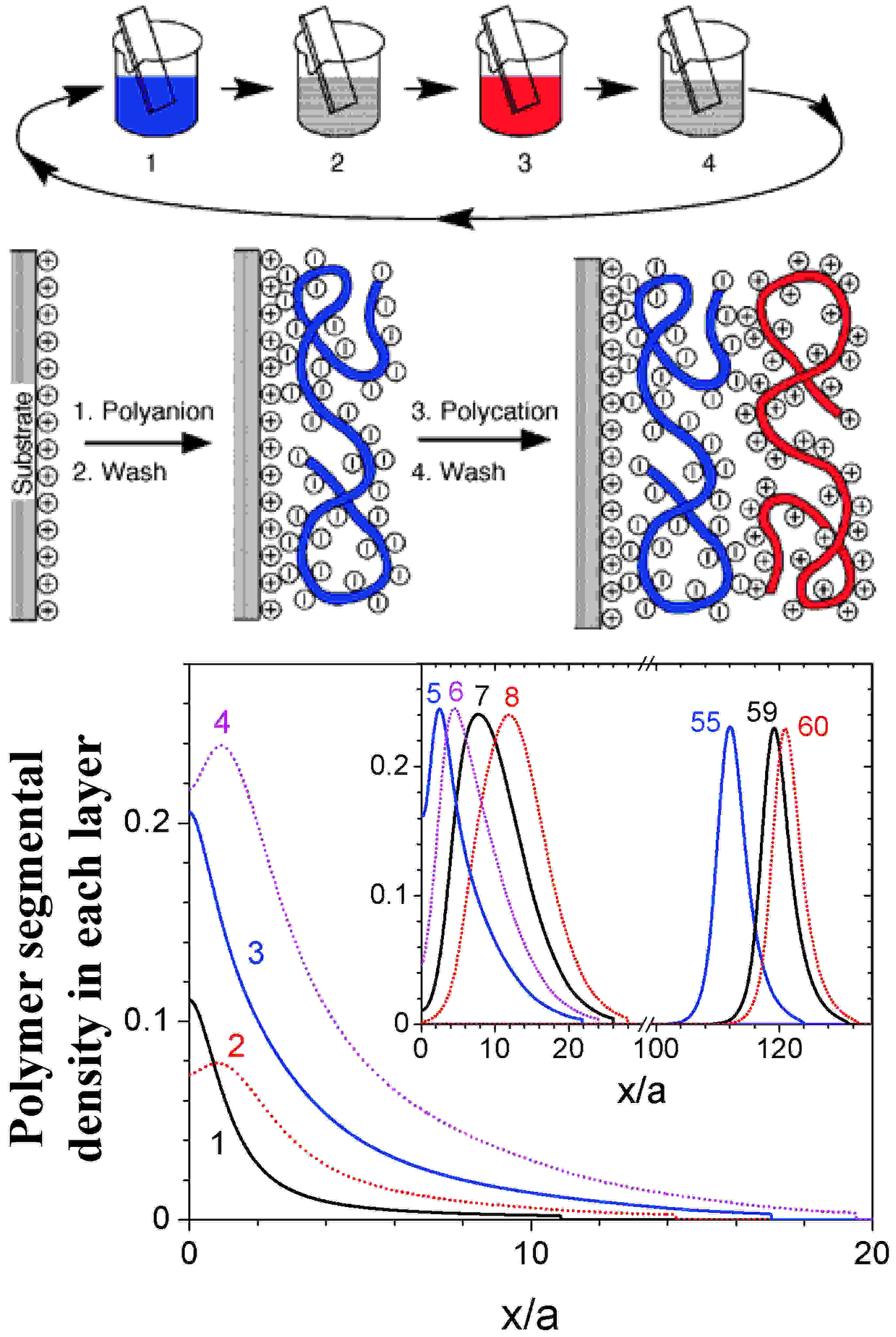

| Polyelectrolyte layer-by-layer (LbL) assembly has attracted exponentially growing interest due to its simplicity, versatility, and great potential for many applications.[13] Our understanding on the formation mechanism, internal structure, and molecular properties of polyelectrolyte multilayer (PEM), however, is still at an early stage. In great contrast to thousands of experimental papers on LbL assembly, very few theoretical and simulation studies have been reported. Although it is known that many parameters (e.g., nature and concentration of adsorbing species and added salt, solvent composition, pH of depositing solution, adsorption and washing time and temperature, etc.) affect the PEM structure and properties, to date there is no predictive tool for even the most basic quantities such as composition, layer thickness, and total charges in the multilayer.

In this ACS-PRF project, we have creatively modeled the LbL assembly process as a series of kinetically trapped states using an equilibrium self-consistent field theory. We have studied the internal structure and charge compensation of PEM formed on flat substrates, and the effects of various parameters affecting long-range electrostatic interactions (including the substrate charge density, polymer charge fractions, bulk salt concentrations) and short-range interactions (including solvent qualities and repulsion between the two polymer species) in the system.[14] Our modeling of polyelectrolyte LbL assembly is in good qualitative agreement with most experiments and molecular dynamics simulations, helps us better understand the formation mechanism and internal structure of PEM, and can further guide experimental design to obtain PEM with desired properties. |

|

|

|

Fast Monte Carlo simulations with soft potentials

We have been very actively developing a class of novel Monte Carlo simulation methodologies, the so-called "fast Monte Carlo (FMC) simulations"[8,12], suitable for the study of equilibrium properties of many-chain systems (e.g., polymer melts) with coarse-grained models. Due to their formidable computational requirements, full atomistic simulations cannot be applied at present to the study of many-chain systems used in experiments. Coarse-grained models have to be used instead, where each polymer segment represents, for example, the center-of-mass of a group of real monomers. While atoms cannot overlap, these coarse-grained segments certainly can. In conventional molecular dynamics or Monte Carlo simulations with coarse-grained models, however, hard excluded-volume interactions preventing segment overlapping (e.g., the Lennard-Jones potential in continuum or the self- and mutual-avoiding walk on a lattice) are commonly used, leading to unrealistic or at best qualitative results.

The basic idea of FMC simulations is to use soft potentials that allow segment overlapping (that is, the repulsion between two coarse-grained segments is finite even when they completely overlap). This results in at least several orders of magnitude faster/better sampling of configuration space than conventional molecular simulations.[8,12] In particular, FMC simulation on a lattice is the fastest molecular simulation method to date.[12] More significantly, experimentally accessible fluctuations can be readily studied in FMC simulations, which are far beyond the reach of conventional molecular simulations.[15] Furthermore, direct comparisons of FMC simulations with the corresponding mean-field (e.g., self-consistent field) theories for the same model system (thus without any parameter-fitting) unambiguously quantify the effects of fluctuations/correlations neglected in the latter.[8,12] Last but not least, quantitative agreement between experimental measurements and FMC simulations even with coarse-grained lattice models can be achieved.[16]

|

|

Systematic and simulation-free coarse graining of polymeric systems

Polymeric systems not only need coarse graining as explained above, but are best suited for it as the large number of monomers on each chain (Nm>103 in typical experiments) allows high levels of coarse graining. In our most recent work on systematic coarse graining, we quantitatively address the issue of how the effective potentials and properties of coarse-grained (CG) models vary with the coarse-graining level l=Nm/N, where N denotes the number of CG segments on each chain. Clearly, larger l means computationally more efficient models. Due to its reduced degrees of freedom (thus chain conformational entropy), however, a CG model cannot exactly reproduce the original system in all aspects. In order to choose the proper l-values, it is necessary to quantify how well the original system is described by CG models with different l, which has rarely been done in the literature.

On the other hand, in most work on coarse graining, molecular simulations (i.e., molecular dynamics or Monte Carlo simulations) are used to obtain the structural and/or thermodynamic properties of both original and CG systems that need to be matched. This is computationally very expensive, particularly for original systems with large Nm (>102) where the statistical uncertainties can be too large for the simulation results to be meaningful due to the difficulty in efficient sampling of configuration space (this is exactly why coarse graining is needed). We therefore recently proposed the simulation-free strategy of coarse graining, where integral-equation theories are used to obtain the structural and thermodynamic properties of both original and CG systems. These theoretical calculations can give quantitatively accurate results and are at least several orders of magnitude faster than molecular simulations.

|

|